Psoriasis is considered one of the oldest skin diseases, with its origins traced to ancient Greece. The Old Testament scribes the biblical term tsaroat, which references a range of skin conditions including leprosy and psoriasis. History reveals that scaling diseases such as psoriasis were often associated with severe illness and its sufferers were subjected to scorn, ridicule, and social stigma. Throughout history, lepers were also considered punished by their affliction and treated cruelly.¹ Psychodermatology explains that in addition to the physicality of psoriasis, sufferers encounter higher levels of psychological distress. Prospective studies confirmed that daily stress triggers increase itching and psoriasis severity and those who worry excessively are the most vulnerable to the impact of the stress-psoriasis connection.⁵ Psoriasis sufferers also report a wide variety of psychosocial symptomology, including depression, low self-esteem, social isolation, interference with daily activities, chronic stress, and potential employment and economic difficulties, as a result of the side effects of psoriasis and the general perceptions of the disease.

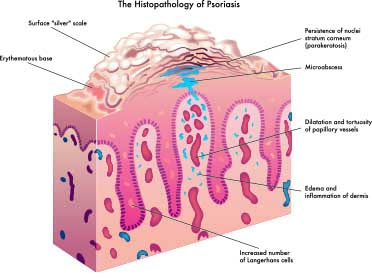

Psoriasis affects skin regions including the elbows, knees, scalp, lumbosacral region, joint flexures, hands, and – in psoriatic arthritis – the joints. Variations in treatment are dependent on the surface area of involvement; the density, inflammation, and thickness of the scales; duration of flares; and other factors. Psoriasis can appear on areas of the skin that have been injured, including vaccinations, sunburns, scrapes, and burns. The epidermis of psoriatic skin displays a defective process of growth and differentiation and an identifiable abnormal permeability barrier. The epidermis often initiates the disease, but there are many contributing factors involving the topical anomalies and systemic influences. Psoriasis presents as a chronic, inflammatory, autoimmune-mediated skin disease affecting up to three percent of the population worldwide. There is a convincing genetic component exhibiting a 33 percent incidence of positive family history and substantial research supporting autoimmune involvement. However, according to the New England Journal of Medicine, “No data supports the notion that psoriasis is a bona fide auto immune disease – psoriasis is probably best placed within a spectrum of auto-immune related diseases characterized by chronic inflammation in the absence of known infectious agents or antigens.”3 The genetic component of psoriasis has approximately 25 gene variants and at least nine substantial chromosomal link factors referred to as PSOR1 through PSOR9. Genomic signatures in psoriatic lesions involve dendritic cells and T cells, interferons, and TNF-a as key cytokines, confirming that cells and mediators of the immune system are significant in the development of psoriasis. Further evidence shows endothelial cells exhibit increased activity in psoriasis through a vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF). Compared to the vasculature of normal skin, psoriatic skin’s microvasculature exhibits leaky blood vessels that contribute to inflamed skin.3

PHYSIOLOGICAL ACTIVITY/IMMUNOPATHOGENIC MECHANISMS

Characteristics can include:

- Exhibiting erythematous, silvery-scaled plaques and the progression of long-term scaling

- Acute onset of small areas of scaly, red patches, along with pruritus or a burning sensation

- Bleeding or petechiae when the skin is scratched

- Unexplained joint pain or pain in fingers, toes, ankles, wrists, and knees combined with skin signs of psoriasis may indicate potential psoriatic arthritis and/or autoimmune disorder

- Chronic presentation of conjunctivitis and blepharitis

- Recent or unexplained viral infection

- Medication reactions to lithium, beta blockers, anti-malarials, and NSAIDs

- Abrupt steroid or corticosteroid withdrawal

- Abnormal activation of cell death pathways leading to inflammation and necroptosis

- T cells and keratinocytes creating the typical, signature, plaque skin lesions

- Defective permeability and barrier function

- Elevated transepidermal water loss up to 20 times greater than normal skin

- Faulty secretion of epidermal lamellar bodies

- Epidermal changes as a result of abnormal circulating T cells

- Disorganization of critical lipids into the extracellular bilayers

- Psoriasiform hyperplasia and elongation of rete pegs4

- Thinned-to-absent granular layer4

- Neutrophil exocytosis, leading to the development of spongiform pustules and collections of neutrophils in the stratum corneum (pustular psoriasis)3

- Potential involvement of B-hemolytic streptococci throat infection4

- Difficulty digesting protein due to poor diet

- Abnormal small intestinal permeability

- Vitamin D deficiency

- Food allergies and sensitivities

- Poor liver function

- Alcoholism15

CLINICAL TYPES OF PSORIASIS

Guttate Psoriasis

This type of psoriasis manifests through small, scaly lesions usually appearing on the trunk, arms, and legs; it may also appear on the scalp, ears, or face and can be triggered by streptococcal throat infection, followed by two or three weeks of skin eruptions. It may resolve itself or evolve into chronic plaque psoriasis. This condition is more common in children and young adults under 30 years old.

Chronic Plaque Psoriasis

Characteristics of chronic plaque psoriasis include inherited systemic inflammation that is immune-mediated, presenting elevated scaling inflamed plaques of scaling, often with intense pruritus. The small scaly patches conjoin to form the larger and marginal plaques. Areas of development include the scalp, elbows, and knees. It can, however, develop on any part of the body. It is the most common form of psoriasis affecting two to three percent of the population in the United States.

Flexural or Inverse Psoriasis

This condition is difficult to treat and is a painful variant of psoriasis that develops in the skin folds, including under the breasts, armpits, buttocks, navel, or genitals. The lesions often appear moist due to the nature of perspiration appearing in the folds.

Pustular Psoriasis

Primarily seen in adults, this form of psoriasis presents blister-type pustules of non-infectious, non-contagious pus. Symptoms may be caused by pregnancy, systemic steroids, overexposure to ultraviolet light, emotional stress, or infections. It tends to be cyclic with reddening of the skin followed by pustular activity. Other variants of pustular psoriasis are von zumbush, palmoplantar (PPP), and acropustulosis psoriasis.

Nail Psoriasis

Nail Psoriasis

Up to 55 percent of people who suffer from psoriasis on the skin may also have nail psoriasis. Nail psoriasis may be due to a combination of genetic, environmental, and immune factors, although the exact cause is not known. Studies have linked nail psoriasis with leukocyte antigen subtypes. Physical characteristics include nail pitting, scaling, and a distinguishing sign of a yellowish-red discoloration resembling an oil drop or salmon patch beneath the nail plate.

Erythroderma

This is a very inflammatory form of psoriasis that may occur with zumbusch pustular psoriasis or may appear on individuals with chronic plaque psoriasis. Presentation and symptomology includes severe redness and shedding of the skin, including large areas of the body; skin that appears burned; increased heart rate; severe itching and pain; and fluctuations in body temperature. This form of psoriasis alters the body’s chemistry, causing protein and fluid loss that can lead to edema, illness, and, potentially, pneumonia or congestive heart failure. Triggers include severe sunburn, allergy mediated rash, systemic steroids, infection, emotional stress, and alcoholism.

Arthropathy/Psoriatic Arthritis/PsA

This condition is an inflammatory response caused by the immune system and may accompany plaque psoriasis. There is also a genetic and environmental component. It can affect any joint in the body and symptoms include swollen fingers and toes, tender and swollen joints, morning stiffness, general fatigue, upper and lower back pain, and reduced range of motion. Variants of PsA include systemic arthritis, distal interphalangeal predominant arthritis, spondylitis, and arthritis mutilan.11

HISTORICAL VIEW

Hippocrates (460-377 B.C.) divided skin diseases into categories: Psora, or itch; lepra or lepo, to scale; and leichen, for scattered scales. Psoriasis was subjected to unusual modes of treatment – both internally and external – including the use of materials such as arsenic, mercury, and snake venom. Hippocrates’ progressive principles discarded notions of religion and superstition and he was the first physician to apply pine tar pastes to psoriatic lesions. Hippocrates also prescribed arsenic, which remained a primary treatment for psoriasis into the middle of the 20th century. It was, however, responsible for the development of pigmentation on the skin, liver, and organs, as well as malignant tumors. Tars of wood origin, to this day, are considered a gold standard treatment by many dermatologists. The tar is cultivated from pine, birch, juniper, or pix betulina and is often used in conjunction with acetic acid, phenol, and carbonic acid. Pine tar has been demonstrated to be antipruritic, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, and antifungal and fractionated pine tar has been said to contain bacteriostatic activity. Although pine tar is widely used, it is not standardized pharmacologically because of its inherent chemical complexity; its exact mechanisms are generally not understood.2

The activity of pine tar appears to be its initiation as a keratolytic agent while inhibiting excessive proliferation of epidermal cells by the suppression of DNA synthesis in hyperplastic skin. This action subsequently reduces mitotic (cell replication) and protein synthesis in the basal layer, encouraging the promotion of keratinization. Studies have further demonstrated that a transient increase in epidermal proliferation occurs during the first two weeks of tar treatment, followed by a progressive thinning of the epidermis and the targeted plaques of psoriasis.2

Although the anti-proliferative effect of coal tars have been studied, it is general consensus that all tars, including pine tar, work in a similar manner. Notwithstanding controversy, older tar product formulations were scrutinized for toxicology concerns, including photosensitization, carcinogenicity, folliculitis, and frequent skin irritations. The majority of the adverse reactions were attributed to formulations pre-1950s, although, as with any product, sensitization and adverse reactions are possible.2

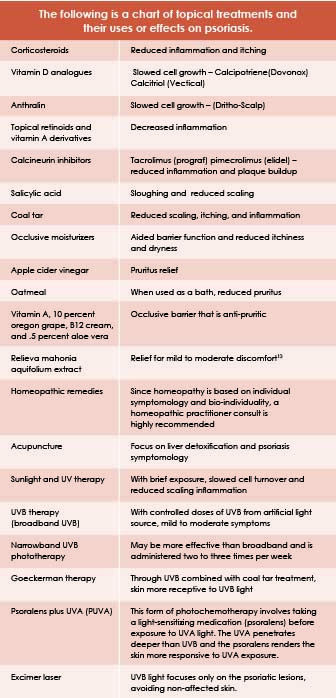

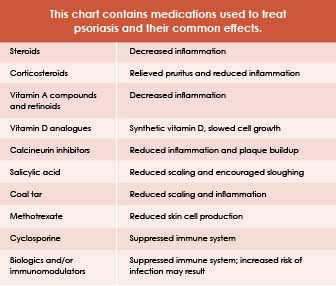

The treatment of psoriasis has been exploratory, arbitrary, and often questionable as to both efficacy and safety since the cure of psoriasis has yet to be discovered. Standardized allopathic treatments have brought relief to many, although trending therapies include nutritional and alternative medicine intervention.

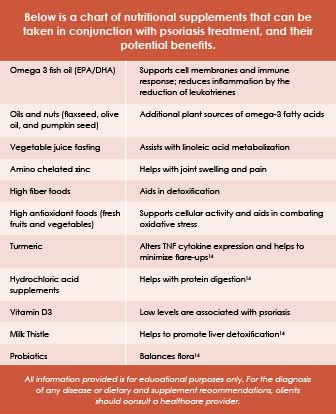

Medications used in the treatment of psoriasis can affect the nutritional status of an individual by interfering with absorption, metabolism and excretions of nutrients in the food.

Sugar, dairy, gluten, alcohol, nightshade vegetables, and foods that are considered inflammatory should be avoided.

Immune status plays a major role in the identification of illness and autoimmune diseases; correlative disorders are on the rise in the United States. A study published in the November 1912 issue of The American Academy of Dermatology indicates that individuals with psoriasis are twice as likely to develop additional autoimmune diseases. These diseases include alopecia areata, celiac disease, scleroderma, lupus, and Sjoren’s syndrome.8 Although the epidermis often initiates psoriasis, there are many contributing factors that instigate systemic manifestations. Continual research identifies that psoriasis is more than skin deep and that there is great significance of the systemic involvement shared with other chronic and inflammatory diseases such as Crohn’s disease and diabetes.3 Collectively, the following comorbidities have been associated with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: altered gut bacteria, cancer, cardiovascular disease, crohn’s disease, depression, diabetes, insulin resistance, leaky gut syndrome, metabolic syndrome, obesity, osteoporosis, uveitis, liver disease, kidney disease, and hearing loss.

The HPA AXIS

The hypothalamic pituitary adrenal (HPA) axis has been implicated in the activity of psoriasis. The activation of neurohormones by stress is predominately via the HPA axis and involves the functioning of several other hormones and stress response mediators. Along with these activities, the release of cortisol occurs, which creates an immunosuppressive effect and directs inflammatory responses. The skin has its own functional and peripheral HPA axis that translates and coordinates the peripheral stress response from the central HPA axis creating the skins

own homeostasis.5,6

INFLAMMATION AND HYPERTENSION LINK

Psoriasis is reflective of systemic inflammation, which places emphasis on the introduction of treatment protocols positioned to address the root causes of inflammation. According to new research conducted at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, patients with more severe cases of psoriasis were more likely to have uncontrolled hypertension. The study also indicated that the likelihood of uncontrolled hypertension increased with the severity of psoriasis.8

The health of the gut is an ever-trending topic and of great significance is the relationship of bacterial flora with regard to integral immunity, hormonal function, and psychosomatic activity. The influx of research connecting the status of the gut flora and the emotional state are escalating, supporting the gut-inflammation connection. The psoriasis sufferer may present candida albicans, signaling that an anti-candida diet or similar nutritional modifications and practitioner-supervised intervention is paramount to restore gut health and address inflammation markers. Research has identified that there are three species of bacterium that are necessary to immune function and are purportedly to be low in patients with psoriatic arthritis: akkermansia, ruminococcus, and pseudobutyrivbrio. Laboratory essays and stool analysis will identify the ratios of “good and bad” bacteria, residing in the gut, as well as C-reactive proteins (CRP), homocysteine, and lipolysaccharides (LPS), which assist to identify inflammatory markers which are of great importance to the identification of inflammation in the body.12 Psoriasis has also been linked to comorbidities such as metabolic syndrome. The explanation for this association lies in the relationship between chronic inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and insulin resistance. Activation of T lymphocytes in psoriasis might be triggered by antigen-presenting cells reacting against an unknown antigen and pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6 or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-a, produced by these cells and may share a pathogenic pathway with obesity and insulin resistance.10

“Approximately 7 million people in the United States have psoriasis- and about 150,000 [to] 260,000 new cases of psoriasis are diagnosed each year- with United States physicians seeing approximately 1.5 million patients per year.”17

Understanding the evolution, identification, and potential intervention methods of psoriasis will greatly help professionals in treating and communicating with clients who have the disease.

References

1. Cowden A., and Van Voorhees, A.S. Introduction: History of Psoriasis and Psoriasis Therapy. Weinberg J.M. (eds) Treatment of Psoriasis. Milestones in Drug Therapy. Birkhäuser Basel. (2008)

2. Barnes, T. M., and Greive, K. A. Topical pine tar: History, properties and use as a treatment for common skin conditions. Australasian Journal of Dermatology, (2016) 58(2): 80-85. doi:10.1111/ajd.12427

3. O. Nestle, M.D., Daniel H. Kaplan, M.D., Ph.D., and Jonathan Barker, M.D. Mechanisms of Disease Frank. New England Journal of Medicine, (2009) 361:496-509. doi:10.1056/NEJMra080459

4. Raskin, C.A. Psoriasis and Apoptosis: A Fundamental Analysis of the Psoriatic Phenotype with Clinical and Therapeutic Correlations. Winkler J.D. (eds) Apoptosis and Inflammation. Progress in Inflammation Research. Birkhäuser, Basel. (1999)

5. Hee-Sun Moon, A. M., and McBride, S.R. Psoriasis and Psycho-Dermatology (2013)

6. Ito, N., Ito, T., Kromminga, A., Bettermann, A., Takigawa, M., Kees, F. Paus, R. Human Hair Follicles Display a Functional Equivalent of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis and Synthesize Cortisol. FASEB Journal. (2005)

7. Gudjonsson, J.E. Immunopathogenic Mechanisms in Psoriasis. Clinical and Experimental Immunology (2004) 135(1):1-8. PMC.

8. Wu, J. I., M.D., Nguyen, T. U., M.D., Poon, K. T., M.S., and Herrinton, L. I., Ph.D. The Association of Psoriasis with Autoimmune Diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, (2012) 67(5): 924-930. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.039

9. Takeshita, J., Wang, S., Shin, D.B., Mehta, N.N., Kimmel, S.E., Margolis, D.J., Troxel, A.B., and Gelfand, J.M. Effect of Psoriasis Severity on Hypertension Control. JAMA Dermatology, (2014) DOI: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.2094

10. Romani, J., Caixas, A., Escote, X., Carrascosa, J.M., Ribera, M., Rigla, M., Vendrell, J., and Luelmp, J. Lipopolysaccharide-binding protein is increased in patients with psoriasis with metabolic syndrome, and correlates with C-reactive protein. British Association of Dermatologists-CED Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. (2012)

11. National Psoriasis Foundation. (1970, January 27). Retrieved from https://www.psoriasis.org/

12. More Than Meets the Eye– Psoriasis And Gut Health. (2017, April 05). Retrieved from https://www.holtorfmed.com/psoriasis-and-gut-health/

13. Bernstein, S., Donsky, H., Gulliver, W., Hamilton, D., Nobel, S., and Norman, R. Treatment of mild to moderate psoriasis with Reliéva, a Mahonia aquifolium extract--a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. (2006) Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16645428

14. Axe, J., DNM, DC, CNS. The REAL Cause of Psoriasis Your Dermatologist Isn't Telling You About. (2018, January 09) Retrieved from https://draxe.com/psoriasis-diet-5-natural-cures/

15. Kazakevich, N., M.D., Moody, M. N., M.D., M.P.H., Landau, J. M., B.S., and Goldberg, L. H., M.D. Alcohol and Skin Disorders: With a Focus on Psoriasis. (2011) Retrieved from http://www.skintherapyletter.com/2011/16.4/2.html

16. “Diseases & Conditions.” Medscape. http://www.emedicine.medscape.com/